by Chantal Khoury

I live for the moving image and its ability to stir a multisensory reaction, but I’m an oil painter for a reason. I make still images. They allow me to unearth, rearrange, and re-present personal archives through a filtered optical lens. Despite my love for film, the 2022 SWANA Film Festival (curated by Christina Hajjar) lingered for days in an open tab on VUCAVU’s website before I watched. It was the first anniversary of my jido’s death. The films offered a range of expressions around complications of loss, longing, and the nuances of retrieval. But there was one film that thrust me back one year earlier to my jido’s Canadian living room.

The day he left Lebanon was the same day he broke the news to his mother; the same day that marked my fate in Canada, and the last day he laid eyes on her as she fell to the floor pleading. Two months before he passed, jido told me his buried shame.

Your Father Was Born 100 years Old, and So Was the Nakba, directed by Razan AlSalah, exemplifies a familiar urgency where artists seek to honour lineage while navigating inherited trauma. In recent months, my inheritance emerged as a million shards from past ruptures that fell onto my skin and pierced through my bones, leaving a tactile, lingering ache. After watching the film, a soothing set in. Despite its full release of sounds and glitch, I witnessed AlSalah’s work as an offering beyond tangible senses.

Jido’s worry beads weighted down my hand. My thumb repeatedly flicked each metal ball across my index, as I studied the greasy sheen left by his fingers. He secretly made them during his first Canadian job at a scrap metal shop. They were heavy, cold, and calming.

The first scene drops onto a point marked “X” within the framework of Google Street View in Haifa. We move through the streets of a digital map that defies all temporal logic, and take the purview of AlSalah’s late grandmother, searching for her past life. “If I can walk, I would find it right away,” she says, reminding us of our geographic severance and how our senses are no longer tools for retrieval. The voice searches for her 100-year-old son, Ameen, calling his name through the static crowds and rubble: “Ameen! Ameeeen!” With a simple script and use of minor technology, AlSalah nudges us toward a subjective, political history, while the grievous voice becomes our collective memory. Attempting and failing to locate her home and son, the frequency of speech escalates with our disorientation, as we enter a seven-minute vertigo. We become caught in her spinning search with no resolution before dropping into another digital frame.

I remember looking for my father’s village and my mother’s childhood home, only to find a distilled allusion to what they may have been. Digital maps are detached from their representations. Like God, we look down from above and choose our desired path until the illusion falls apart once we try to enter a window, turn on a switch, burrow in a bed, walk off a static cliff, catch a fly, or clutch a branch until our hands can’t grip the mouse any harder.

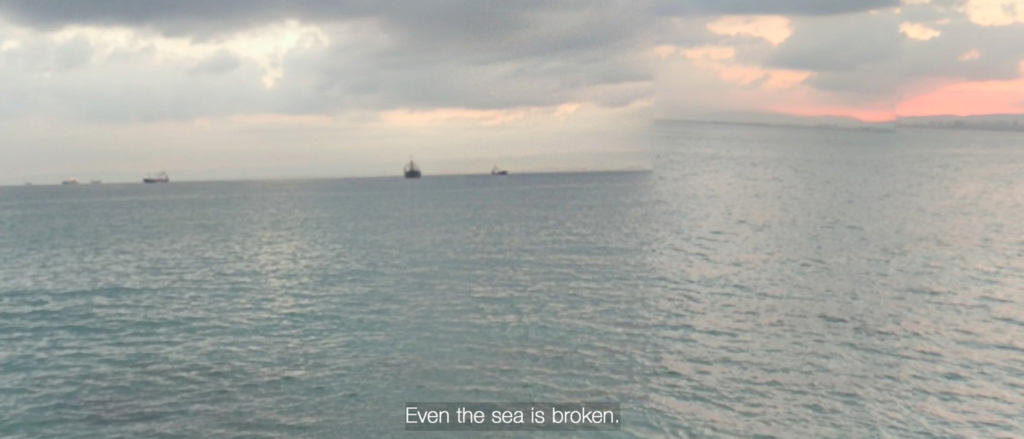

AlSalah breaks the film into three distinct digital landscapes, leading us to the final scene of a rupture in the sea’s horizon—the last notes from our guide: “Even the sea is broken. There is no escape.” Although a split horizon is not possible, the image embodies a true depiction of lived experiences in exile.

AlSalah probes our senses and leaves us on the line between truth and doubt, inclusion and exclusion. The film left me questioning, while nearly grasping at the answers: How do we separate ancestral memories from lived ones? We don’t because we can’t. How do we speak of gratitude after loved ones are gone? We speak through them. Your Father Was Born 100 years Old, and So Was the Nakba offers a genuine and poetic take on negotiating loss and navigating presence outside of a linear narrative. The screen becomes a contemporary portal that replaces the ancient arch—you don’t know whether you are entering, returning, or leaving something behind.

The weight of metal beads grew heavier through changing hands—a tactile reminder that each erasure leaves a mark.

Postcolonial theories and methodical painting techniques frame Chantal Khoury’s practice. Of Lebanese descent and born on the unceded territory of the Wolastoqiyik/Mi’kmaq First Nations/New Brunswick, she lived in Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montreal before relocating to Ontario in 2019. Collections include the RBC, the AGG, and UNB.